It was during construction work near the Karja manor in 1949 that 18 skeletons with an array of old artefacts were uncovered. As it turned out, the construction had cut into an ancient cemetery that was later, in 1955, excavated by the archaeologist Aita Kustin. By that time, part of the cemetery was already under a building but fortunately it was still possible to excavate most of the site. The original size of the cemetery was approximately 400 m2.

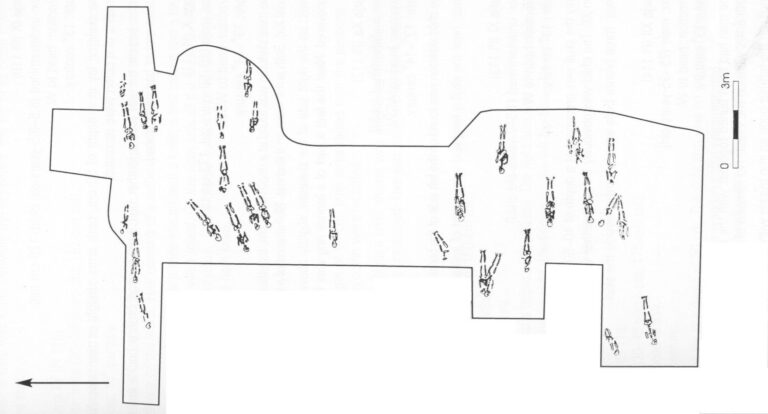

Altogether 34 skeletons were found during the archaeological excavations, however, according to Kustin, the cemetery may have contained as many as 70 burials. All the deceased were interred with their heads to the west, and several graves had remnants of coffins, all indicating a Christian burial. Located in the middle of the cemetery was an empty area with no skeletons that may have been occupied by a wooden chapel. Based on the artefacts and coins found in many graves, the Karja cemetery is dated to the 13th–14th centuries.

The people buried in the graveyard were Christians. Its location in the middle of arable lands and right next to the manor house built somewhat later suggests it might have been a small Christian cemetery adjacent to a private church or chapel. The first aDNA analyses reveal that most of the deceased were not closely related, and represented the whole congregation. Some of them were probably members of the small vassal family who had erected the church or chapel.

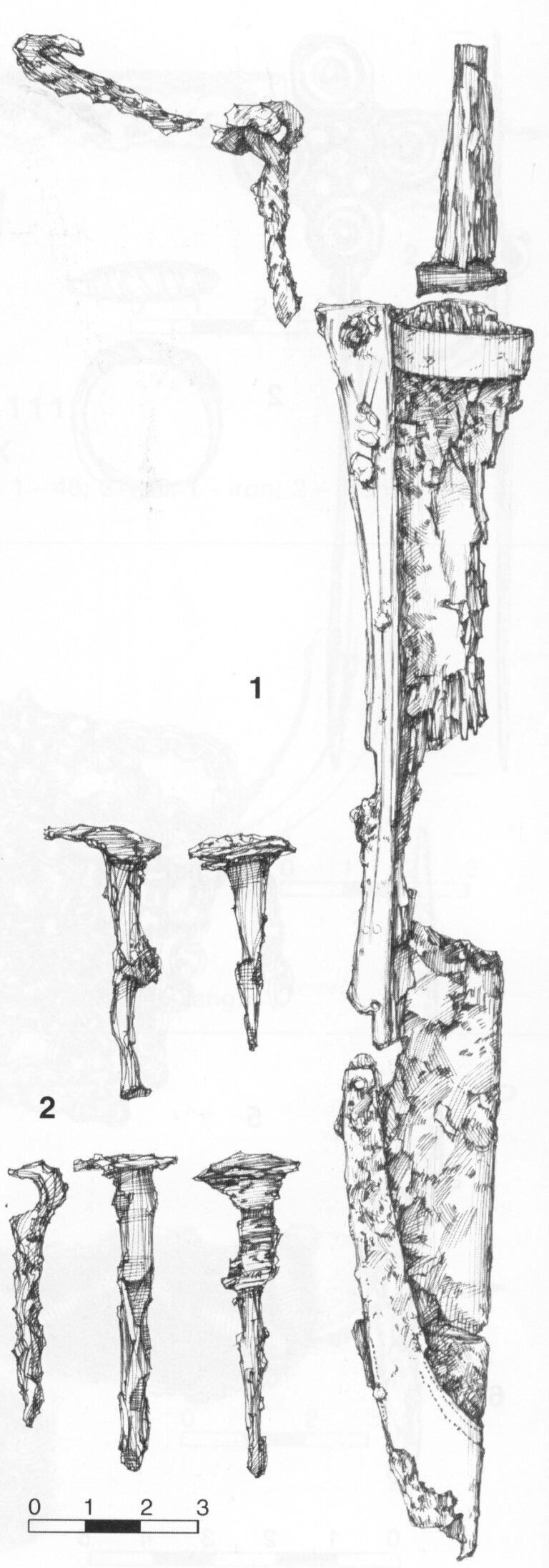

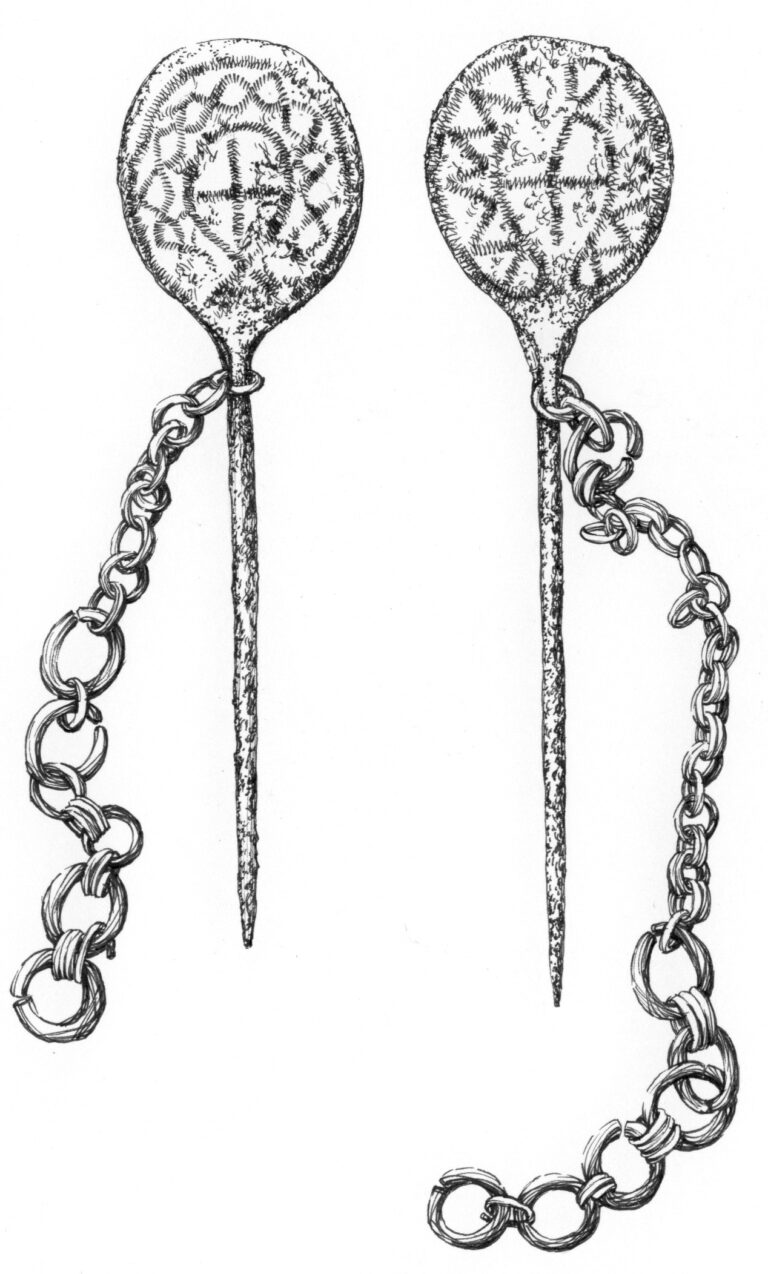

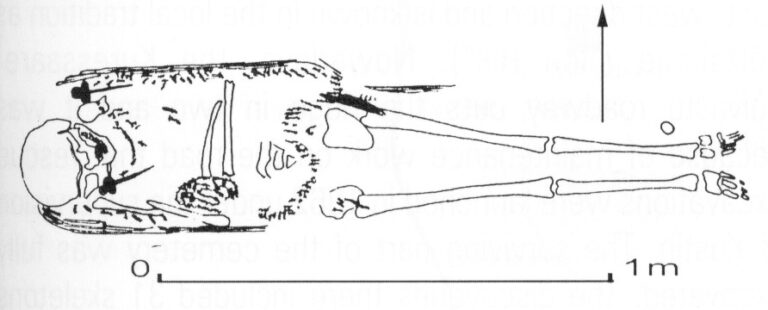

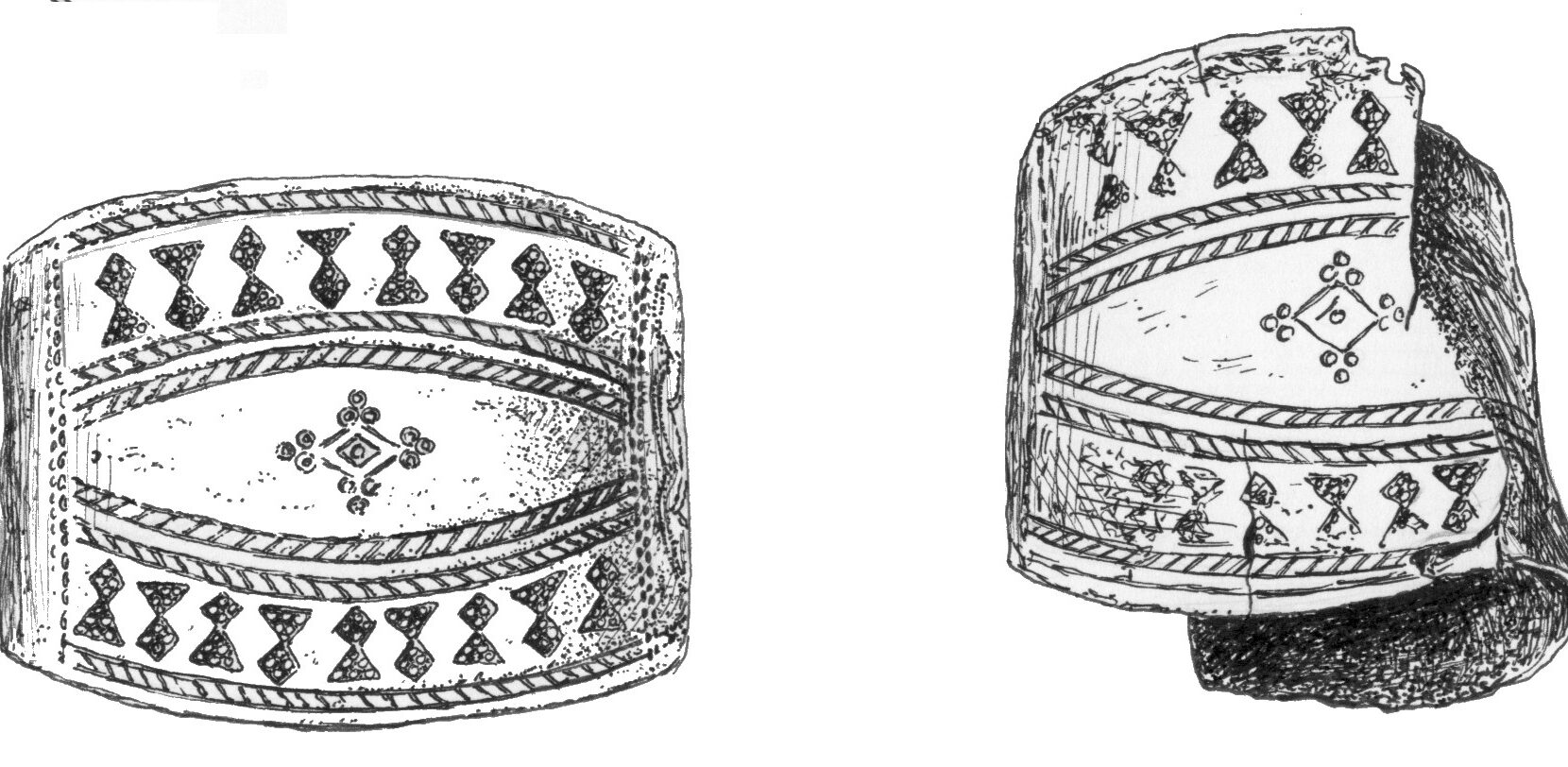

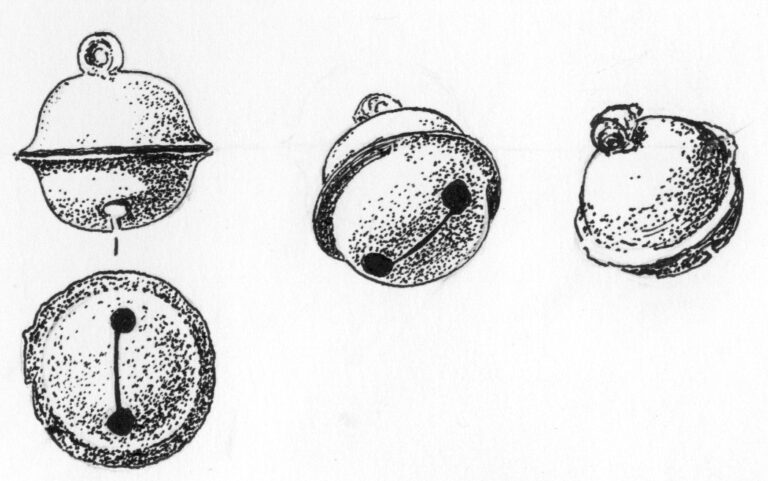

Artefacts, especially jewellery, were mostly found in female graves, whereas male graves were furnished very sparsely. This of course applies to exclusively metal items capable of surviving 600–700 years. Even if once present, fine fabrics and clothing with embroidery or fur cannot survive that long. Nevertheless, pieces of cloth were found attached to metal ornaments which helped to preserve textile – some of the deceased had been buried in clothes decorated with bronze spirals and rings. Such ornaments were characteristic of women’s aprons and shawls. Some females were wearing dress pins or chain sets locked upon the shoulders with penannular brooches, and some had rings on their fingers. Most of the jewellery and clothing decorated with bronze details were not on the deceased but inside the coffins and under the bodies. The most common grave good for males was a knife, occasionally found inside a bronze-lined scabbard and connected to the belt with a chain of iron links. The belt itself was fitted with a bronze or iron buckle.

Out of the 34 skeletons, 13 belonged to males, 10 to females, and 11 to children. Six females and two males had died between the ages of 35 and 50, and three females and six males were older than 50, which by the standard of those days was already ripe old age. Four males died at the age of 25–35.