Kaali is mostly known for its meteorite craters, of which the biggest crater is surrounded by the eight smaller ones. The fall of the meteorite is dated quite differently. According to the latest knowledge, it must have happened during the second half of the Bronze Age or at the end of it, around 1600-1800 BC. To put it simply, the devastating effect of this event on already densely populated Saaremaa can be compared with the catastrophic results of a smaller nuclear bomb. The meteorite flew towards Saaremaa from the East, and must have been visible from all coasts of the northern half of the Baltic Sea. It is believed that the survivors may have interpreted the event as the death of the Sun, that more that the dust caused by the explosion presumably overshadowed the daylight, perhaps for several days.

Even though the lake of Kaali is nowadays thought of mostly as an ancient holy site, it was not known as such in local folklore until the beginning of the 19th century. The idea of the holiness of the site was first invented by some Baltic German scholars in the 19th century, and spread from their writings to the local population, thus creating secondary folklore. Nevertheless, we cannot say for a fact that the lake was never a holy site. The place may have been perceived sacred in the end of the Bronze Age or in early Iron Age, but usually, the collective memory does not extend that far back.

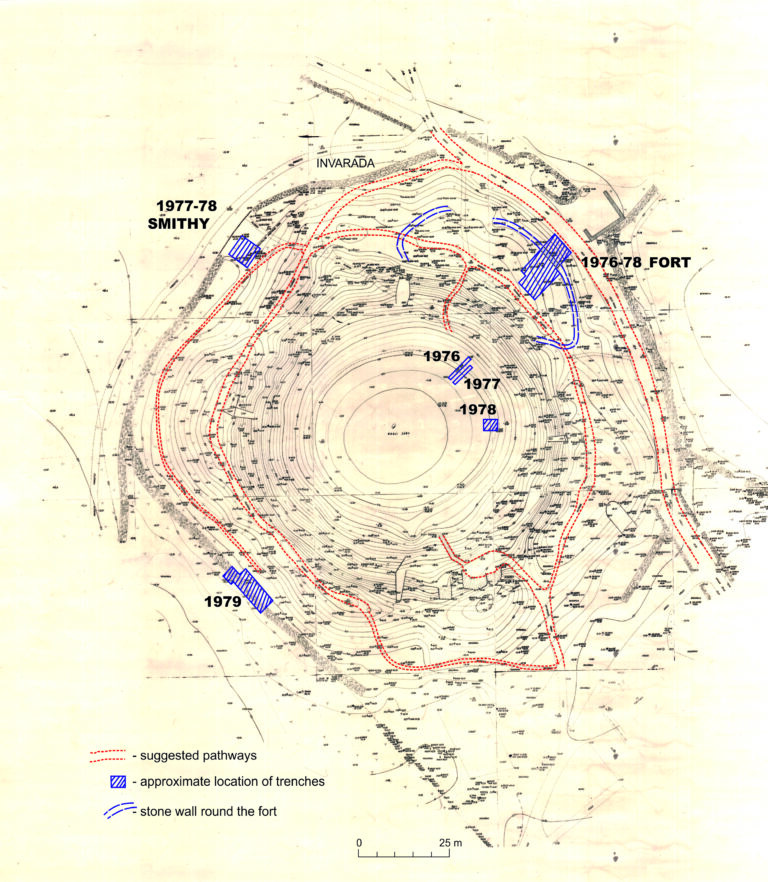

Archaeological excavations in and around the Kaali Lake were conducted 1976-1979 by Vello Lõugas. Unfortunately, the results were poorly documented and only briefly published. A fortified settlement site with a semi-circular layout was discovered on the northeast side of the main crater. Ceramics and single metal items dated the earlier use of the site to the second half of the Bronze Age, the 8th-6th century BC, while most of the finds seem to belong to the pre-Roman Iron Age, 500 BC – 50 AD, and, according to Lõugas, possibly also to the 3rd-4th century AD. 14C analyses taken from the settlement site of Kaali also denote the period from the end of the 6th century until the 4th century BC, thus the end of the Bronze Age and the pre-Roman Iron Age. The unusual location of the site speaks for the theory that it probably was a sacred complex.

The area of the fortified settlement was altogether 800 m2 and as is seen from the remained part, when viewed from the outskirts of the crater wall, it used to be surrounded by a limestone drywall, 2 m wide and 2.5 m in height. The excavation area in the middle of it was around 135 m2. At least two square stone platforms were discovered from the yard. Similar stone platforms have been later recorded in other sites, for example at the Tõnija Tuulingumäe cult place. Lõugas interpreted the Kaali platforms as foundations of buildings. Additionally, five or six remarkably big granite boulders were uncovered between the platforms at Kaali. Another stone platform, similar to the ones inside the walls, was also located outside of the presumable fortified settlement. Burnt layers were discovered both sides of the wall as well. A wooden construction had probably been on top of the stone wall and destroyed by fire.

Other examples suggesting the cult function of this site are a silver deposit consisting two spiral bracelets and a neck-ring, and another separately founded silver finger-ring. These ornaments can be dated to the long period between the 5th century BC and the 5th century AD. Indeed, such artefacts are quite unusual finds at regular early Metal Age settlement sites.

In 1978, a small-scale excavation was conducted in the lake of Kaali, which was pumped dry for this reason. The works stopped when the depth of the digging was around 4 m, due to crisscrossed tree trunks that had fallen into the lake. According to dendrochronological analyses, the lowest tree trunk was an oak that had started to grow in the year 1181 and had fallen into the lake in 1426.

Probably in the pre-historical period, perhaps even in the same time when the presumable fortified settlement was in use, the lake of Kaali was surrounded by a massive stone wall, which foundation was 2.3-2.8 m wide. In 1979, a 10 m long excavation cutting through it indicated that there was no cultural layer outside the wall. However, plentiful bones of domesticated animals (oxen, horses, pigs, lambs, and dogs), mainly skulls and teeth, were found from the inward area, probably indicating one-time offerings. Prehistoric pottery was found on the level above the animal bones, and by this, Lõugas dated the building of the circular wall to around the beginning of our era.

The circular stone wall and the earlier foundation under it.

In 1977, remains of a smithy were discovered from the shore of the lake, and dated to the 17th-18th century. Even though Lõugas mentioned the possibility of prehistoric iron working at the same place, there is no decisive proof to show for it. Nevertheless, iron slag has also been found in the southeast area of the wall around the lake. It is unknown, when and for what reason did it end up there.

The Kaali complex has been interpreted and dated differently. The fortification used for a long be interpreted as a Bronze Age fortified settlement. Modern archaeologists define it as a cult site from the end of the Bronze Age and the beginning of the Iron Age.