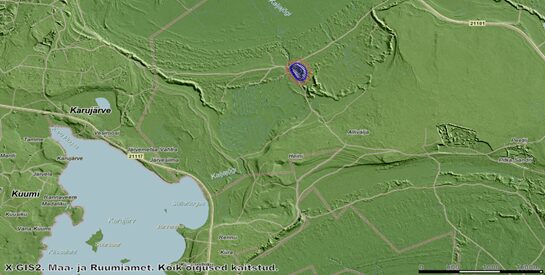

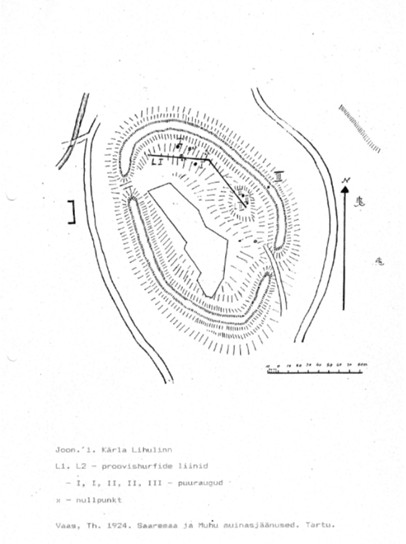

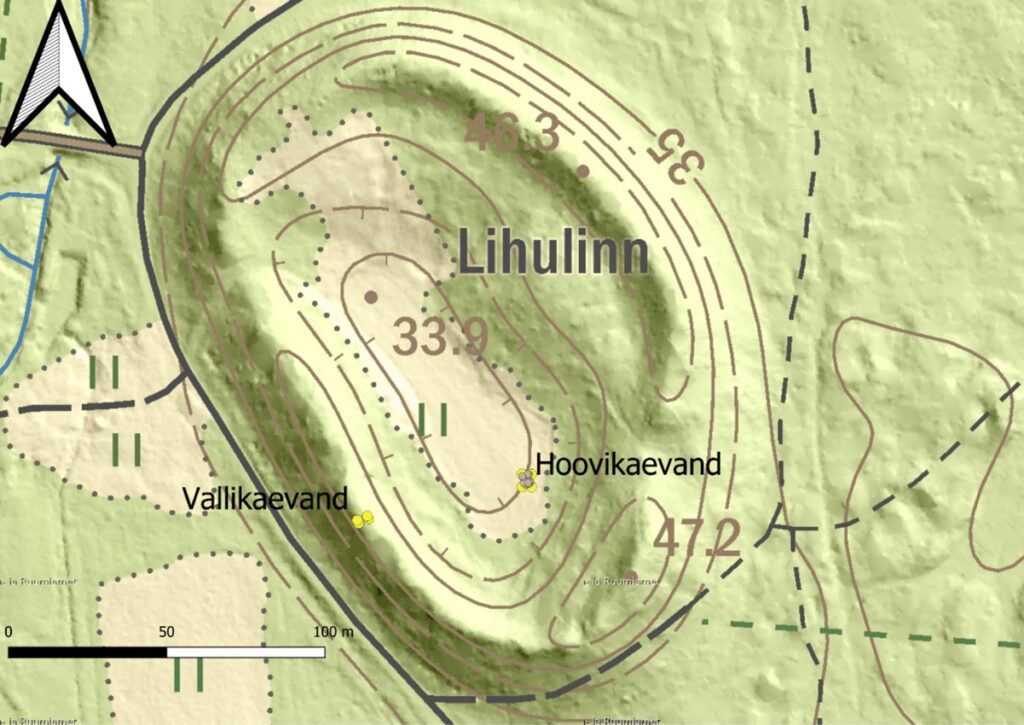

The Kärla hillfort, also known as Lihulinn, is the largest prehistoric stronghold in Saaremaa. It is in Western Saaremaa, only two kilometres northeast of Lake Karujärv. The hillfort measures approximately 270 metres northwest–southeast and 170 metres northeast–southwest, with an estimated courtyard area of 1.8 ha. In constructing the stronghold, natural sand dunes were used, upon which powerful ramparts were built, rising 7–10 metres above the outer ground level.

In the 18th century, the Kärla hillfort was mentioned under the name Leolin or Lehren Stadt, which has also been associated with the name Lõo(kese) linn.

The courtyard of the hillfort is divided into two parts: the northern and northeastern sections lie on a higher natural sand elevation, while the southern and southwestern parts occupy a lower area. The lower flat section has historically been used as farmland – in the early 20th century, a well pit with walls made of fieldstones was reportedly still visible there during ploughing.

In 1984, a forest fire occurred on the hillfort, and sand was taken from the northeastern rampart for extinguishing fire, which is why this section of the rampart now has an uneven appearance. In the same year, small-scale test excavations were carried out by Evald Tõnisson and Ülle Tamla. These excavations revealed that the lower area of the stronghold has a cultural layer 10–20 centimetres thick. Traces of the cultural layer were also found in the higher northeastern part of the courtyard. In the upper part of the northeastern rampart, which was examined to a depth of up to two metres along the edge of an earlier pit, burnt stones and multiple layers of charcoal were uncovered.

In 1992, archaeologist Jüri Peets, in cooperation with geologists, carried out geological investigations at the hillfort. Among other things, a hole was drilled on top of the rampart. It was found that the mixed material containing charcoal and burnt sand extends to a depth of 5.3 metres. The rampart is heaped from sand and stones onto the natural dune. Within the mixed sand are darker layers and charcoal patches; the hillfort seems to have experienced three major fires. At a depth of roughly 160 cm, a compact charcoal layer 5–8 cm thick was encountered. Below this layer were larger stones. At 175–200 cm depth, another darker, charcoal-flecked layer resembling cultural soil appeared, under which again was lighter sand with darker charcoal streaks. The last, third layer lies at 330 cm depth and consists of an intense 10–12 cm thick burned layer of charcoal. Below that, at 530 cm, the soil turns lighter and natural.

In 1995, archaeologist Jüri Peets conducted archaeological excavations in the northeastern part of the hillfort, on the higher plateau. It was found that the cultural layer was 15–25 centimetres thick and contained handmade pottery and finds dating to the 11th–13th centuries, while radiocarbon dates also indicated the 9th–10th centuries. During the excavations, many burnt stones were discovered, possibly from earlier fortifications or buildings, as well as several pits with mixed layers and a few possible post-holes.

Small excavations at the hillfort were carried out in 2025. The aim of these was to study the lower area of the Kärla hillfort using a 3×4 metre excavation, to clarify the period of use of the stronghold and the nature of the cultural layer. The main research question was whether the investigated area had been overbuilt during the hillfort’s period of use. Additionally, a 0.5×3.5 metre trench was opened on top of the rampart to obtain a charcoal sample for dating the hillfort’s last fire and refining the end of its period of use.

The courtyard excavation yielded several Late Iron Age artefacts, including pottery, flint pieces, beads (including a gold-foil bead) and animal bones. In the deeper layers of the trench, a shallow pit filled with stones and a possible post-hole were revealed, which may indicate a former structure or temporary building, although their function remains unclear. Similar pits have also been observed in Jüri Peets’s previous studies.

From the rampart trench, charcoal samples were obtained that make it possible to date the hillfort’s last fire. Based on preliminary results, it can be said that the rampart is made of stones and sand, and on top of it there was some form of wooden fortification.